The good food revolution: Race, economics, and what local means with Detroit activist and educator Malik Yakini

More than 130 residents and community leaders gathered in Battle Creek, Michigan late March for the second annual good food summit.

A highlight was the keynote by Detroit-based activist and educator Malik Yakini. Malik is a passionate advocate—equal parts warmth and warrior. And while he is a champion of the good food revolution, Malik sees the work as part of a larger movement for freedom, justice, and equality.

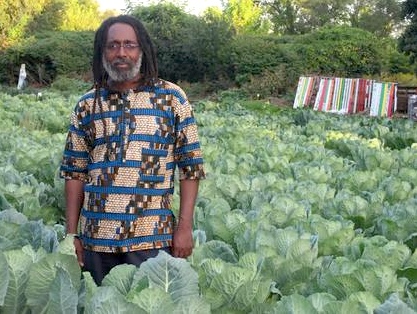

Malik Yakini, chair of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, at D-Town Farm. Photo by Catherine Porter & City Farmer News

Malik’s resume includes more than 20 years as principal of a K-8 African-centered school in Detroit along with the recent founding of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, which works to build self-reliance, food security, and justice in Detroit’s Black community.

We caught up with Malik following his keynote to dig deeper into themes of race, equity, and economics.

You speak powerfully on the importance of race in food justice. Why is this critical?

So-called race is a huge factor along with class and place in determining the extent to which communities have access to high quality food. The reality is that race still impacts all major institutions in American society.

That should stand to reason given that we are only 238 years into the American experiment that was founded on the theft of Native American land, the enslavement of Africans and a legal system designed to give privilege to white men.

We can’t have a just food system without addressing the system of white supremacy.

Detroit Black Community Food Security Network’s

D-Town Farm during Harvest Fest

Local ownership is another theme of your work. Why is this important, especially in a community like Detroit?

Some people will respond to the arguments made about how localism can build local economies. We must vigorously inject this concept into the public discourse.

Most people, however, will respond to seeing how local ownership in the food system makes their lives better. If localism can actually create more jobs, create better access to fresh produce, and circulate wealth in distressed communities, then many people will be won over.

On the other hand, if localism is not guided by the values of justice and equity, it can reinforce the divide between the haves and have-nots and support gentrification.

This is the challenge in Detroit.

Much of the new development in Detroit takes place in the most highly gentrified areas, while most neighborhoods are left to languish.

The most effective movements grow organically from the people whom they are designed to serve. Detroit’s majority Black population must be in the leadership of efforts to foster food justice and food security in our community.

The Detroit Black Community Food Security Network works to build self-reliance, food security, and justice in Detroit’s Black community. A key part of this is cooperative economics. What does this mean?

Co-ops are a very old strategy employed by African Americans to lift ourselves up in a society with multiple structural barriers. Mutual aid societies were used to sometimes buy loved ones out of chattel enslavement. In the post-reconstruction era and through the 20th century, Black farmers formed co-ops to purchase land, seeds, and tools, and to work and sell their harvest collectively. Blacks throughout the United States also formed co-ops to start grocery stores, butcher shops, housing, and land.

So co-ops are not a new strategy, but they are still a critical way to galvanize our collective power.

In 2008, the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network started the Ujamaa Food Co-op Buying Club, a monthly buying club offering healthy food, supplements, and household items at discounted prices. Today the buying club has more than 230 members – with 40 new members joining in the first two months of 2014 alone.

Now we’re working very hard to create a co-op grocery store in Detroit’s North End Community. This store will stand in sharp contrast to the many stores that function as wealth extraction stations in our community. We hope to break ground on it in 2015.

You’re a vegan and organic gardener. What’s your ideal meal?

My ideal meal is a raw kale salad and a brown rice stir fry with veggies fresh from my garden.

What keeps you going in this work?

I remain hopeful that we have the capacity to transform ourselves and our communities. My spirituality compels me to strive for truth, balance, harmony and justice.

Dig Deeper.

Learn more about Malik and what’s happening with the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network in past Fair Food Network blog.

For more on the good work happening in Battle Creek, check out their Facebook page.