The key difference between what poor people and everyone else eat

September 23, 2015

Source: Washington Post

Author: Roberto A. Ferdman

The good news is that the nearly 50 million Americans who participate in the food stamp program are getting as many calories in food, on average, as everyone else.

The bad news is that those calories are coming from much less healthy things.

Researchers at the UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, hoping to evaluate the current state of the largest federal food assistance program in the United States, reviewed 25 different studies published between 2003 and 2014. Each of the studies analyzed data on the dietary quality, food choices, and spending habits of both those who use food stamps, known as the Supplementation Nutrition and Assistance Program (SNAP), and those who don't.

The findings, published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, are, in some ways, surprising. Soda consumption, for instance, has long been believed to be particularly high among poor people, but it turns out that may not be correct.

"Based on this study, there's actually pretty mixed evidence that this is true, which is probably why people looking for evidence to support their view that participants drink more or less soda than average have been able to find it," said Tatiana Andreyeva, who is the lead author of the study. "To be honest, this was fairly surprising for me. I expected to see clear evidence that both soda purchases and consumption were higher."

The report is also revealing in that it shows how effective the program has been in its goal to alleviate food insecurity. In terms of energy and nutrient intake, food stamp users appear to be doing all right. They neither consume too few or too many calories. In fact, their intake is roughly on par with both poorer and wealthier Americans who are not part of the program.

"Their caloric intake does not systematically differ from that of income-eligible or higher-income nonparticipants," the study notes.

"If you just look at calories or a lot of other nutrients, there’s actually no significant difference," said Andreyeva. "People in the program are getting enough to eat, which means that it's definitely helping."

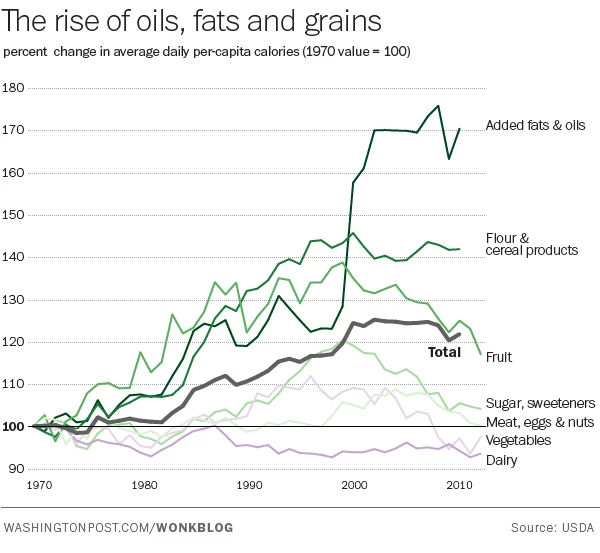

But just because people are eating, doesn't mean they're eating well. For one, suffice it to say that consuming food like the rest of America isn't necessarily a pathway to health. The average person living in the United States eats some 2,600 calories-worth of food each day, far more than was the norm not long ago. And that increase has come largely from the rise of oils, fats, and grains.

What's more, the most sobering part of the study's findings is that food stamp program participants, though they might be managing to muster as many calories as everyone else, are putting food on their plates that is substantially less healthy than even the current, uninspiring American standard.

The average American scores only a 58 out of 100 on the Healthy Eating Index, a metric devised to health gauge the quality of any given person's diet. The average food stamps participant, however, scores only a 51 out of 100, according to one study cited by the review, and 47 out of 100, according to another.

"Americans are pretty poor eaters, but SNAP participants have particularly bad diets," said Andreyeva. "They don't eat nearly enough fruits or vegetables, and they consume too many fats and sugars."

Part of that, Andreyeva says, is due to the fact that participants are, by virtue of their qualifications, extremely pressed for cash. They eat fewer meals as a result, and select for more caloric foods, which tend to be less healthy, in order to adjust. Starch-heavy meals, fattier fare, and sugary foods all tend to be cheaper.

Part of it, however, might also be driven by the absence of free time to cook foods which require longer prep times (often vegetables). Convenience, in other words, can be a diet killer.

All in all, though, the program is helping millions of Americans make due. It's also helping to underscore a problem that is quintessentially American. While obesity is a problem that many countries are coping with, it's an epidemic that is normally characteristic of more opulent portions of society. The growth of countries tends to give way to the growth of waistlines. And the poor are normally the last to suffer from the epidemic.

But here in the United States, just the opposite is true. Contrary to international trends, including those observed in other developed countries, poor people in America are far more prone to obesity than any other demographic.

There are many efforts to reverse this trend, including the re-uped National School Lunch Program, which has disallowed the serving of various unhealthy foods in schools, like chips and sugary drinks, and required the inclusion of others, like fruits and vegetables. There are also movements to incentivize produce purchases by SNAP participants, including the Double Up Food Bucks program, which allows members to spend twice as much money at farmers markets.

Still, the food divide seems to be headed in the same, disconcerting direction that wealth inequality has.

"So far, the healthy eating movement has mostly changed the eating habits of wealthier Americans," said Andreyeva. "My worry is that over time the gap between the dietary quality of SNAP participants and non-SNAP participants is going to widen."

The wealthy, in other words, will continue to eat better and the poor won't. And the gap between them will only become more difficult to bridge.

Roberto A. Ferdman is a reporter for Wonkblog covering food, economics, immigration and other things. He was previously a staff writer at Quartz.

First posted at Washington Post on Septbember 17, 2015.